The Old Conflict Brewing in Europe The Farmers’ Protests and the Future of Europe

- Kevin Skarin

- Mar 3, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: May 14, 2025

by Kevin Skarin

An old conflict is brewing once again in Europe. The fields that fuel the European economy lay dormant with immense challenges plaguing the future. Instead, the streets of European capitals are filled with tractors, and manure is being sprayed on government buildings in defiance by the farmers. At the same time, we see the climate crisis worsening, consumer prices rising, and a war in Europe. Considering these challenges, European governments must decide where to delegate their limited funds and political capital. They must walk a fine line between accommodating these political challenges in a limited capacity, so as not to alienate any group. As the farmers’ protests show, their issues have been largely “forgotten” and, in that sense, they are already alienated from their country's administration. This instability must be extinguished before it becomes a larger issue that can’t be contained. History has shown that heightened polarization and radicalization have the ability to lead to destruction, and it is therefore in Europe's best interest to pacify further polarization. With this old conflict rearing its head at this formative moment in history, European governments must act now to secure the future stability of Europe.

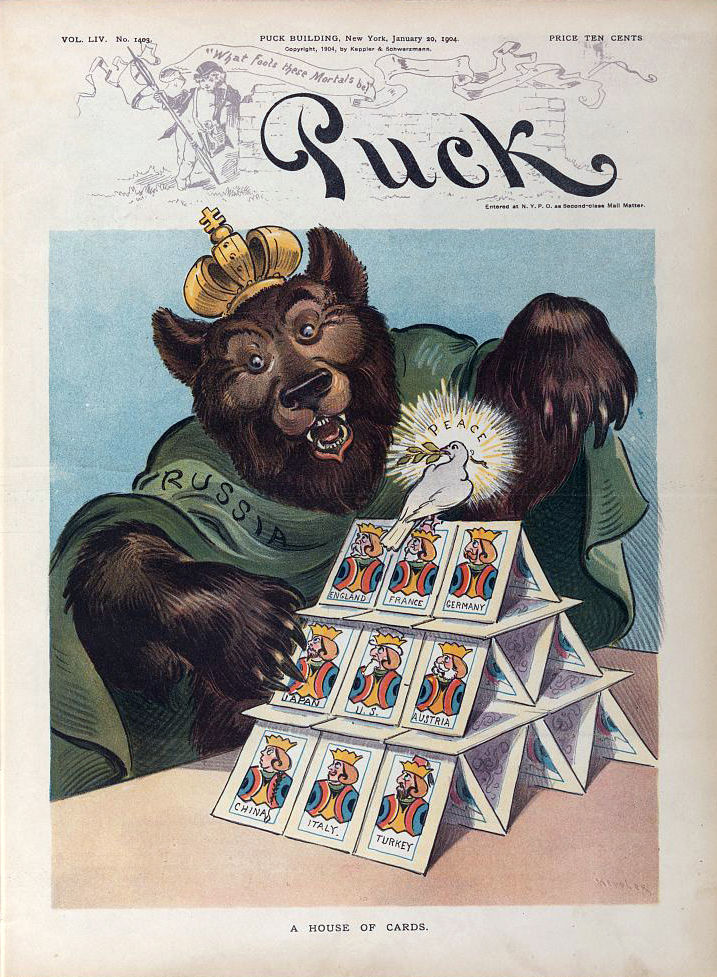

The recent agrarian protests in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France are not as new of a phenomenon as some may think: they are echoes of a melancholic symphony that played during one of the most crucial moments in human history. After World War I, farmers faced an international agrarian crisis because of the war and an abnormal price structure of grain. For countries with poorer soil quality such as Germany, this meant a drastic recession for the agricultural industry. When the Great Depression hit Europe in 1929, it meant an increased downturn where many lost their jobs and livelihoods. This radicalized the farmers and led many of them to protest in a similar fashion to what we are seeing today.

These protests had a wide ideological background. For example, there was the Rural People's Movement in Germany, which emerged in 1928 and was considered an extremist right-wing movement that grew out of the international agrarian crisis and alienation of the German government. This movement laid the foundation for the Nazi Party and its rise to power. In contrast, the Nordic countries which, unlike Germany, had an already strong agrarian movement, decided to take a more pragmatic approach to their interests. In the cases of Denmark and Norway, agrarian parties had already come to power by the early 1900s and had solidified agrarian interests in government policy long before the international agrarian crisis. They also had a social-liberal ideological background and were forerunners of democratization in these countries. In Sweden, agrarian interests were solidified in government policy when the Social Democrats and the Agrarian Party(today the Center Party) decided to work together in a coalition government. They came to a quid pro quo agreement that stipulated that some agrarian policies and some social democratic policies would be implemented. This meant that the radicalization that was seen in Germany never became as extreme in the Nordic countries, where agricultural interests were sufficiently represented in the government. The agrarian protests today are as ideologically diverse as those we find in history. From the populist dissent in Germany to the pragmatic movements in the Nordic countries, history unfolds a narrative of the economic hardship faced by farmers back then and now.

The interests of European farmers have always held a large sway in national and EU politics. In 2022, the EU spent €54 billion in agricultural subsidies, which amounts to about 30 percent of its budget. This is called the Common Agricultural Policy, and it has been one of the most important programs of the Union and its biggest expense. It is a subsidy program that directly supports farmers, invests in rural regions, and stabilizes the agricultural market. This has been a lifeline for the deprived rural regions which cannot cope economically without the subsidies, and has meant that agrarian issues have been met and there has been no need for further action. However, the resurgence of protests in recent years may suggest that these measures are not as effective in meeting the needs and expectations of the farmers of today.

The COVID-19 pandemic shook the international economy to its core. It has meant that the agricultural industry needed more subsidies from national and international governments to sustain the loss of income. Because of the pandemic, the international supply chain was interrupted, which made certain agricultural input goods, such as fertilizer, more expensive and forced farmers to raise their prices. This became a major issue because of the decreased demand for agricultural produce from restaurants, many of which closed their doors during the pandemic. This meant that farmers had a surplus of agricultural produce and could not raise their prices as it would mean even less demand. Small-scale farmers were hit particularly hard for these reasons.

After the pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine once again created supply chain problems for farmers. Russian fertilizer exports to Europe have drastically decreased as an effect of the war, which has made fertilizer more expensive. In solidarity, Europe opened its market to Ukrainian agricultural exports to keep their farmers afloat as their exports through the Black Sea were stopped by Russia. This meant that Ukraine's agricultural produce, which can be made more cheaply because of Ukraine's soil and less regulations, has now been competing with what EU farmers produce. Consequently, this means that EU farmers have less money to run their businesses and less income to live on.

Another issue for rural farmers is the perceived and actual divide between rural and urban populations. The globalization effect on the economy has identified the clear “winners” and “losers” of globalization. The “winners” are the urban populations, which take a greater part in the global economy and reap a greater benefit than the rural population. This has, in some part, led to larger economic inequality between the “poor farmers'' and “rich urban elite". Unfortunately, this meant that the rural populations in the most advanced economies have shrunk and been largely “forgotten” by the political elite. This is one of the main talking points for populist politicians, who divide society into the “moral good people'' and the “evil elite” to further their political aims. Populist politicians will therefore want to use the anger felt by the rural population to gather support for their ideological aims. While this argument is true in some sense, it is also true that EU and national governments have spent a lot of resources on these rural regions. The perceived divide between the rural and urban populations is seen as a bigger problem than it might be in reality. This is in large part because of populist politicians and polarization. Since there is ambiguity about what the true problem is, farmers are more inclined today to mobilize around a shared issue as they perceive it.

As mentioned previously, European governments have a lot on their plates. They must tackle a cost of living crisis, deal with a recession, help Ukraine fend off Russia, build up their own armies and, as the cherry on top, stop global warming. These combined issues are very costly, and governments must decide which is the most urgent to attend to. Many of them see the subsidies for farmers as costly and bad for the environment. Therefore, the German, Dutch, and French governments have decided to cut back on farming subsidies such as diesel and have put in higher nitrogen restrictions to save costs and to protect the environment. The German government, with its fiscally conservative policy, wanted to cut back on diesel subsidies for farmers so they can invest in a green economy. By doing so, the hope was to jump start a sustainable green industry that would create new jobs and opportunities. Something that European governments failed to predict was the farmers’ reactions to these cuts and higher restrictions.

Already struggling farmers cannot cope with these changes and see that the only alternative is to protest if they want to continue farming. All of these factors have meant that European farmers have once again been mobilized for a common cause. The main issue today is the preservation of their livelihood. If this anger is left unchecked, populist politicians might use it to gather more support for their extremist ideologies and their political aims. An extreme version of this process is found in the inter-war German case, where farmers' discontent was channeled by populist politicians to further their destructive political aims. That is not to say that all agrarian movements are extremist, but there is a clear risk of radicalization if their issues aren't met appropriately.

What does the future hold for European governments and farmers? With a worsening socio-economic situation in Europe, it is very likely that we will see more agrarian turmoil across Europe. Additionally, as the agrarian agenda has become a transnational movement across the EU, more farmers will be mobilized to demonstrate when they see other successful demonstrations. This has already happened, with new protests spreading across Spain, Italy and Greece. To pacify the unrest, European governments should choose to focus on agrarian reform, which will in turn mitigate the radicalization of farmers. The problem, as we have seen throughout history, is that European governments have found themself in a position where they do not have the political or fiscal resources to satisfy the demands of farmers because of many global and domestic issues plaguing Europe, i.e. tackling climate change or the war in Ukraine. In this case, European governments can try to reduce the polarization between the urban and rural populations through symbolic acts, such as making small-scale, publicized investments in rural areas. Mainstream parties should try to include more agrarian concerns in their agendas, as it might remove some of the populist talking points that radicalize them. The farmer's issues can’t be ignored, as it will only spur on the movement further and lead to further radicalization. If the parties are unable to adjust their strategies, they will risk losing stability in core democratic institutions, as seen in Germany in the 1930s.

If European governments want to avoid this destructive political development, they could look at the pragmatic approach taken by the Nordic countries during the early 1900s as inspiration. By pragmatically working with the agrarian movements to tackle the challenges of the times, the Nordic countries kept polarization to a minimum. They accommodated both rural and urban interests in working together and could therefore mend the ties between the groups. This is not an easy feat to accomplish today because of the polarization in European society. A pragmatic approach is less viable if both camps don't want to cooperate. Someone has to take the first step to be able to work together, and that someone should be the governments that leads us. They must lead by example, they have to both work with the agrarian movement and tackle the challenges of the times to secure stability in the future. The old conflict is only a threat if it’s ignored, our governments have an obligation to secure future stability for all citizens, even those they do not agree with.

Comments